Over the last ten years, there have been reports of the publishing industry cracking down on professors who make copyrighted work available to students, a practice they estimate costs them nearly $20 million a year. As James O’Neil with Bloomberg News put it, “The conflict stems from the interpretation of ‘fair use.’” Considering how difficult fair use is to interpret and how technology has opened the door to presentations and projects using multiple medias, this conflict has started to affect a lot more than just textbooks.

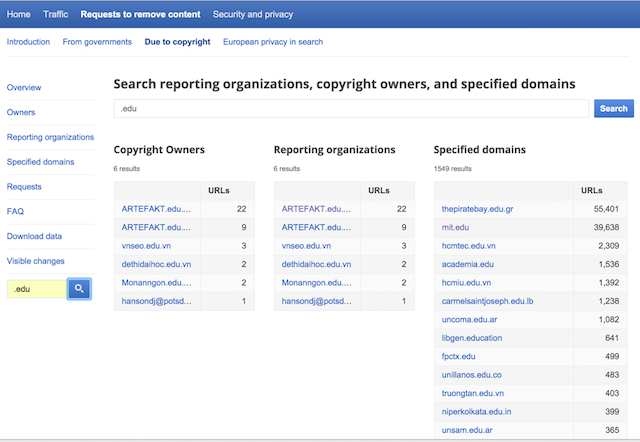

Google publishes transparency reports allowing anyone to see which sites have been reported for copyright infringement, and .edu domains are far from safe. Major universities such as NYU, The University of Texas at Austin, UCLA, and MIT have a median takedown request of 2 URLs per week. MIT in particular received a huge number of requests just in the last year, almost 40,000 URLs, stemming mostly from BPI (British Recorded Music Industry) Ltd. Not surprising considering how fuzzy the guidelines are for professors and students wanting to share music, movies, and images that fit a certain subject.

Screenshot of Google Transparency Report: Search results for ".edu"

Screenshot of Google Transparency Report: Search results for ".edu"

To help clear up some of the basic questions, we made a breakdown of who can claim fair use, when, where, for what, and why.

Who Can Use Fair Use?

University professors often believe that “educational usage” allows them carte blanche, but as Patricia Aufderheide wrote for insidehighered.com, “Working non-commercially does give you some privileges, but you’ll be stuck in a gray zone if you depend on that to justify fair use.” That said, commercial or non-profit remains the most important distinction in determining fair use. So start with a simple question when you are not sure if you can copy materials: are you sharing content with students just in the classroom or will you be profiting from this work in any way?

What Does Fair Use Apply To?

With a rise in multimodal learning, a lot of what you might want to include in PowerPoint presentations or projects will be copyrighted, like images found on Google, all movies, or portions of a text whose author hasn’t been deceased for at least 70 years. For the most part, it’s safer to assume that the work you want to use is copyrighted and claiming fair use will need to be based on other factors, like intent.

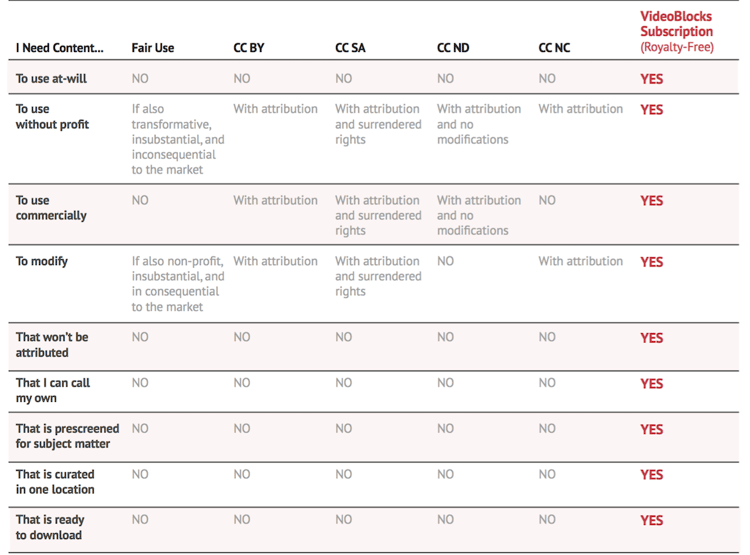

Some materials, however, will let you off the hook if they have a Creative Commons license, common for images and videos found on the internet. This distinction means that the copyright owners have waived their rights as long as you follow certain conditions. These materials will have a code alerting you as to how you can share the work:

- Attribution (CC BY): You can use the material as you like as long as you credit the original owner.

- ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): Same as attribution, but with the stipulation that your version of the material have the same license.

- Attribution NoDerivs (CC BY-ND): You can share the material as you like, but you cannot change it in any way and must credit the original.

- Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC): The same as attribution, but cannot be used in any for-profit situations.

When and How Can You Use Materials Through Fair Use?

The important timing element with fair use is not so much when you use a copyrighted work, but how much of it you are going to use. Generally, the shorter the film clip or sound bite, the better chance you have of claiming fair use. There are other stipulations to consider though, like “digital locks,” meaning you can show a short portion of a DVD to students, but you should not alter the material itself digitally because editing a movie to just the right amount of time would be too easy. This means that if you have multiple clips to show, you should put the DVD in, show the first clip, take it out, put in the next, and so on.

Where can you claim fair use?

Similar to the idea of commercial versus non-profit, another factor of fair use depends on the effect your copy will have on the market, whether or not you personally profited. Even if you haven’t turned your classroom into a movie theater, making materials available to the point that they discourage students from purchasing that material on their own can infringe copyright and does not qualify for fair use.

Like the professors targeted by the publishing industry, sharing through the internet opens up a lot of new possibilities for infringement, as you can make copyrighted material available to anyone, anywhere. For students and teachers alike, sharing materials on the internet versus in the classroom will come down to whether you’ve affected the copyright owner’s ability to make money.

Why are you using the material?

Criticism, commentary, reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research won’t count as infringement as long as the use of the material is transformative. Meaning that why you are using this material could be as important as anything else. Confusingly, showing a science class an action movie and asking them to analyze it might be fine under fair use while simply playing them a documentary on black holes could be considered infringement.

Organizations such as, the Center for Social Media, have tried to establish clearer codes and practices for multiple disciplines like Cinema and Media studies, but even then there is still room for interpretation and the possibility of creating problems by allowing students to post work they have created with other medias online: “For example, students may use copyrighted music for a variety of purposes, but cannot rely on fair use when their goal is simply to establish a mood or convey an emotional tone.”

There has to be a new, special reason for copying this material that differs from its owner's intention. In court cases and policy standards across universities, this idea of transformation often provides the most dispute over what is and is not fair use.

An Alternative Solution

Cutting out the time necessary for professors and students to justify using copyright material or fit the necessary requirements for creative commons, royalty-free digital media libraries offer content that can be used, shared, and modified with no constraints.

Image from VideoBlocks Edu eBook: Campus Guide to Copyright (download here).

With the VideoBlocks EDU Digital Backpack, students and teachers can easily find relevant content, edit to fit their needs, call it their own, and even use it commercially if they want without worry of infringing on copyright protections or needing to justify fair use.

If you would like to learn more details about the rules for fair use and how much simpler a royalty-free library makes sharing content, check out our in-depth ebook on the topic, Campus Guide to Copyright.